Braddock Pennsylvania

Case Study

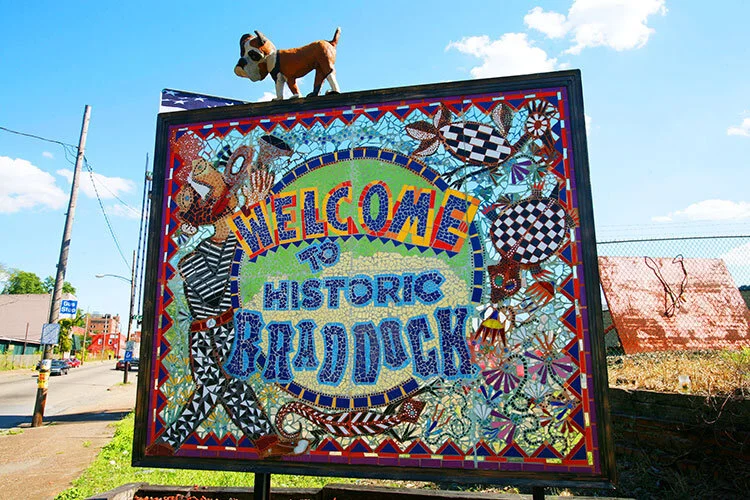

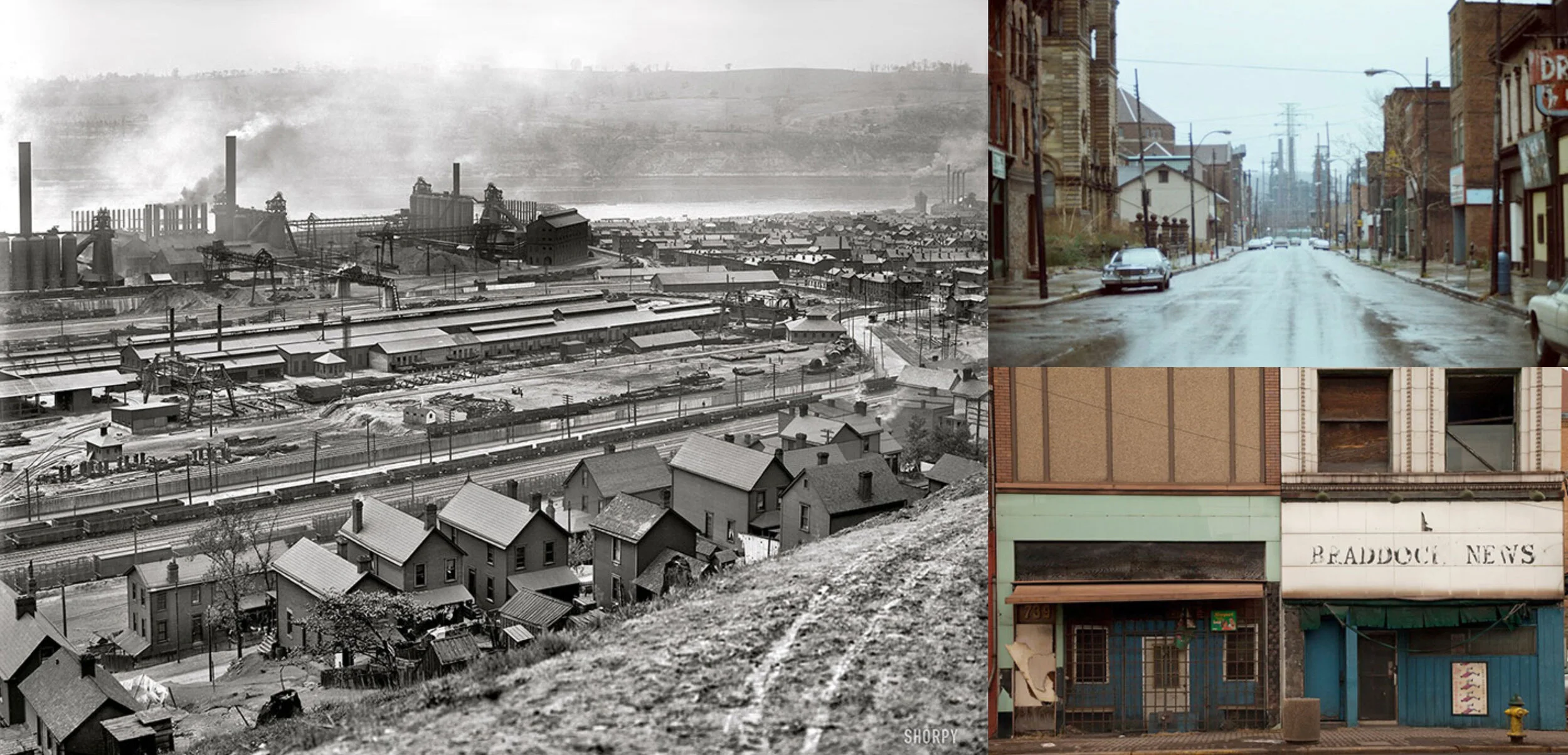

A developing example of a remarkable regeneration drive in the US is that of Braddock, Pennsylvania. Once a thriving steel town, Braddock represented the middle-class American Dream. Andrew Carnegie’s first steel mill and first Carnegie library were built in Braddock. For decades, working men flocked to the town eager to create a better life for their families.

The Eighties were unkind to Braddock when the steel mill (which employed tens of thousands) was shut down. Those who could afford to leave did just that, and what was once a prosperous community of 20,000 dwindled to an impoverished district of fewer than 3,000. Unemployment soared, as did its common bedfellow, crime. Murder rates grew to three times that of the national average, and before long 90 per cent of the buildings were dilapidated or derelict, with a median house price of $4,000

In 2005, the residents of Braddock elected a 6-foot-8-inches, 300-pound, tattooed, goatee-wearing Ivy League-educated renegade as its mayor. John Fetterman won by one vote in a three-candidate Democratic primary. I’m guessing the voters of Braddock have never heard of Russell Brand’s ‘voting changes nothing’ theory! Nothing about Fetterman is conventional.

The scion of a wealthy established Pennsylvanian insurance mogul, he looks more at home in the Hells Angels than the boondocks of Braddock. He and his wife bought the most expensive house in Braddock for $16,000, moved in, and set about helping to rebuild this broken community one project at a time.

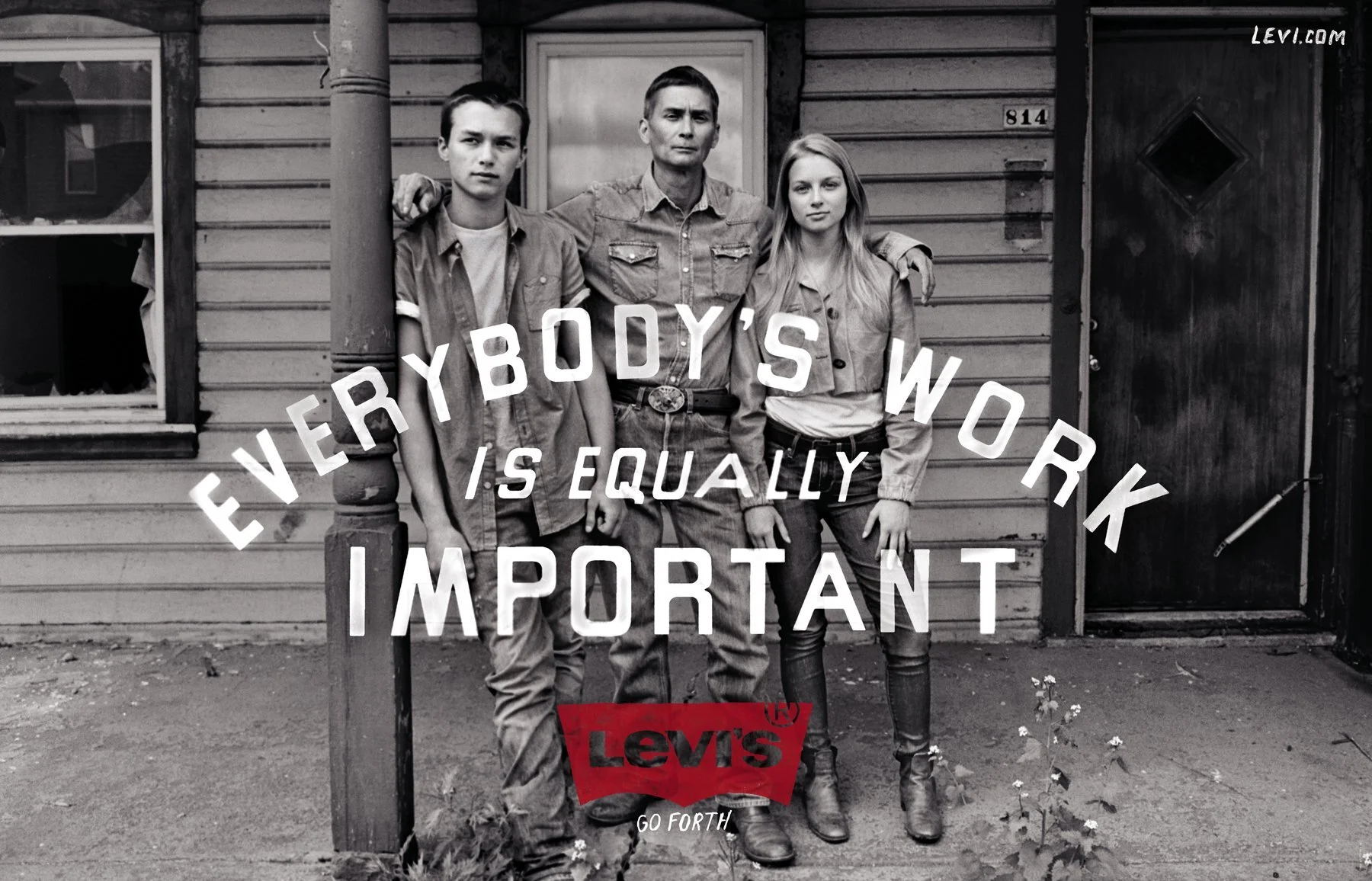

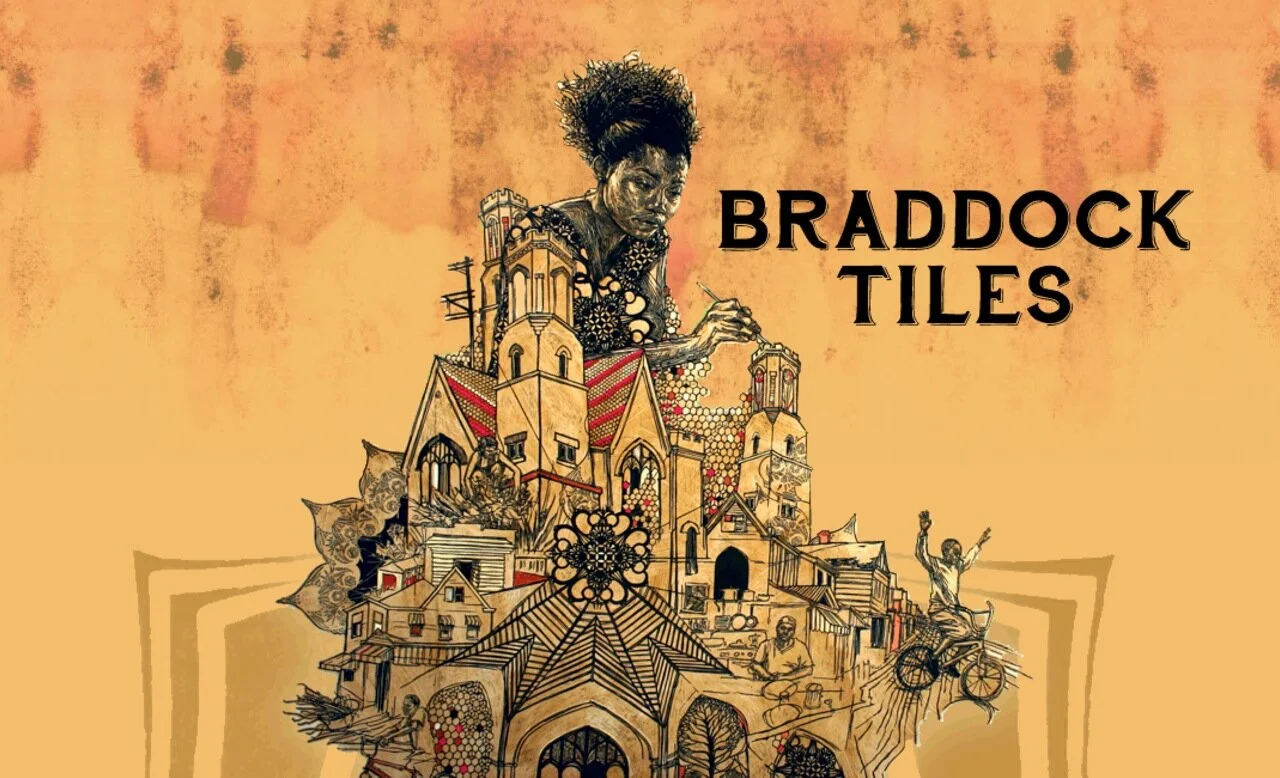

Within five years, Fetterman was able to bring Braddock national attention, encouraging millions of dollars of outside investment, including a global advertising campaign by Levi Strauss. But how did he do this? In a 2011 interview with the New York Times, Fetterman commented: ‘We’ve lost 90 percent of our population and 90 percent of our buildings ... 90 percent of our town is in a landfill. So we took a two-pronged approach. We created the first art gallery in the four-town region, with artists’ studios. We did public art installations. And, I don’t know if you consider it arts, exactly, but I consider growing organic vegetables in the shadow of a steel mill an art, and that has attracted homesteading.’

The scion of a wealthy established Pennsylvanian insurance mogul, he looks more at home in the Hells Angels than the boondocks of Braddock. He and his wife bought the most expensive house in Braddock for $16,000, moved in, and set about helping to rebuild this broken community one project at a time. Within five years, Fetterman was able to bring Braddock national attention, encouraging millions of dollars of outside investment, including a global advertising campaign by Levi Strauss. But how did he do this?

In a 2011 interview with the New York Times, Fetterman commented: ‘We’ve lost 90 per cent of our population and 90 per cent of our buildings ... 90 per cent of our town is in a landfill. So we took a two-pronged approach. We created the first art gallery in the four-town region, with artists’ studios. We did public art installations. And, I don’t know if you consider it arts, exactly, but I consider growing organic vegetables in the shadow of a steel mill an art, and that has attracted homesteading.’

In just nine years Fetterman’s results have been astounding. The statistics speak for themselves:

The estimated Braddock Hills crime index is 58% lower than the Pennsylvania average, and the Pennsylvania crime index is 22% lower than the national average.

The estimated Braddock Hills violent crime rate is 64% lower than the Pennsylvania average, and the Pennsylvania violent crime rate is 9 percent lower than the national average.

The estimated Braddock Hills property crime rate is 57% lower than the Pennsylvania average, and the Pennsylvania property crime rate is 24% lower than the national average.

Braddock Hills is safer than 81.9% of the cities in the nation. The crime rate in Braddock Hills is less than 74% of the cities in Pennsylvania.